In my last post I extolled the virtues of the histogram and proclaimed March “Hug a Histogram” month. It seems only fitting then that I dedicate another post or two to the benefits of using histograms – and the costs of not doing so.

I recently came across a great, real world example in Michael Lewis’s wonderful book, “The Big Short,” which tells the story of a few, very sharp individuals who foresaw the pending collapse of the mortgage securities market and made a fortune betting on its inevitability.

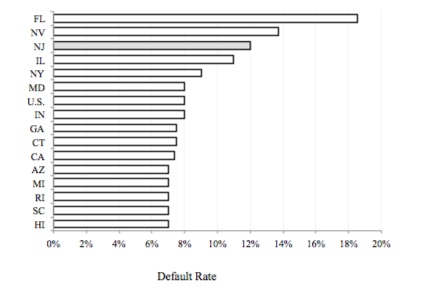

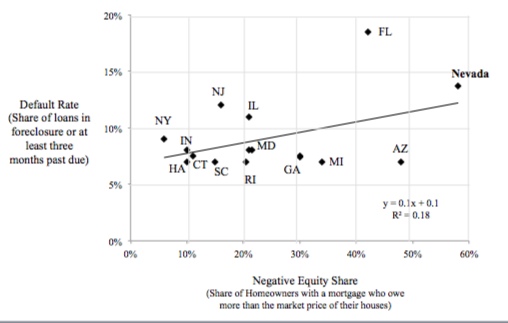

As Lewis tells the story, mortgages were being moved off the books of banks, packaged together into bonds, then sold to investors. The price of those bonds depended on the rating agencies’ assessment of its risk, which they calculated by taking the average FICO score of all its underlying mortgages (a FICO score is a numerical assessment of the credit worthiness of the borrower). If the average FICO score was 615 or higher, the bond received the highest possible rating (AAA). It didn’t matter the distribution of the individual FICO scores in the bond, the rating agencies cared only about the average. Yes, the AVERAGE.

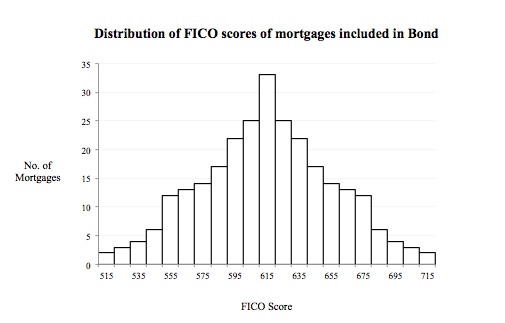

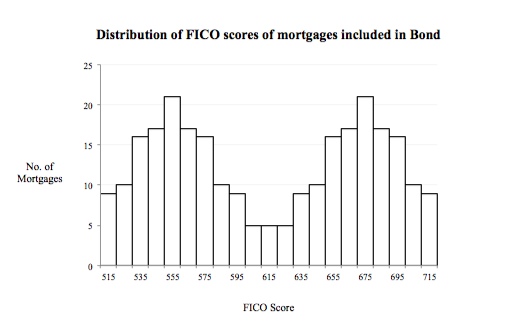

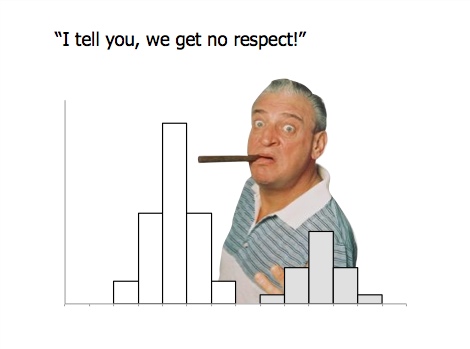

Under this approach, two bonds with the following distribution of FICO scores were both rated AAA.

Clearly, these bonds have very different risk profiles – the “hump” of mortgages representing low FICO scores in the second makes it much likelier to default. And, of course, many just like it did! Yet the agencies saw average FICO scores of 615 and rated both AAA. And thus more and more mortgages were packaged and sold – wash, rinse, repeat – with investors blind to the risk all the while. What a mess.

Please, make the histogram part of your analytical tool kit. The costs of not doing so can be very painful!